Travis CI started out as an idea, an ideal even. Before its inception, there was a distinct lack of continuous integration systems available for the open source community.

With GitHub on the rise as a collaboration platform for open source, what was missing was a service to continuously test contributions and ensure that an open source project is in a healthy state.

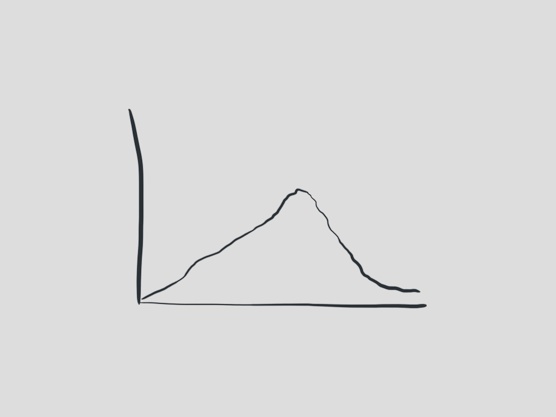

It started out in early 2011, and gained a bit of a follower-ship rather quickly. By Summer 2011, we were doing 700 builds per day. All that was running off a single build server. Travis CI integrated well with GitHub, which is to this day still its main platform.

It didn’t exactly break any new ground on the field of continuous integration, but rather refined some existing concepts and added some new ideas. One was to be able to look at your build logs streaming in while your tests are running, in near real time.

On top of that, it allowed configuring the build by way of a file that’s part of your source code, the .travis.yml rather than a complex user interface.

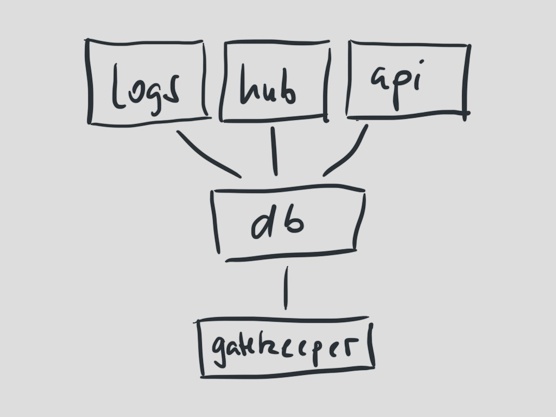

The architecture started out very simple. A web component was responsible for making builds and projects visually accessible, but also accepting webhook notifications from GitHub, whenever a new commit was made to one of the projects using it.

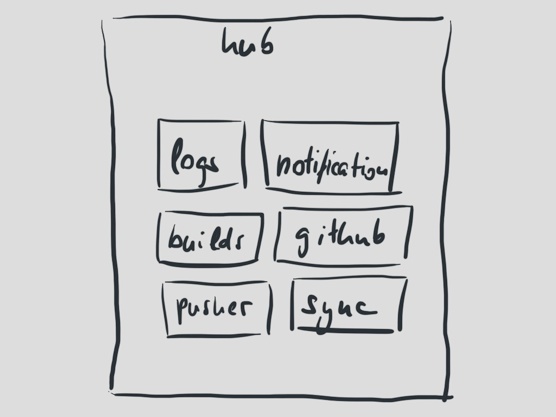

Another component, called hub, was responsible for processing new commits, turning them into builds, and for processing the result data from jobs as they ran and finished.

Both of them interacted with a single PostgreSQL database.

A third set of processes handled the build jobs themselves, executing a couple of commands on a bunch of VirtualBox instances.

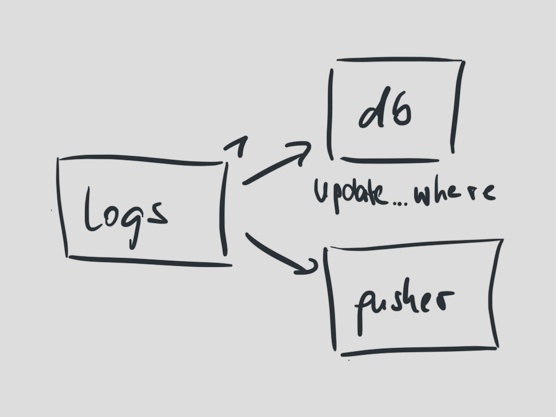

Under the hood, hub was slightly more complex than the rest of the system. It interacted with RabbitMQ, where it processed the build logs as they come in. Logs were streamed in chunks from the processes handling the build jobs.

Hub updated the database with the logs and build results, and it forwarded them to Pusher. Using Pusher Travis CI could update the user interface as builds started and as they finished.

This architecture took us into 2012, when we did 7000 builds per day. We saw increasing traction in the open source community, and we grew to 11 supported languages, among them PHP, Python, Perl, Java and Erlang.

With gaining traction, Travis CI became more and more of an integral service for open source projects. Unfortunately, the system itself was never really built with monitoring in mind.

It used to be people from the community who notified us that things weren’t working, that build jobs got stuck, that messages weren’t being processed.

That was pretty embarrassing. Our first challenge was to add monitoring, metrics and logging to a system that was slowly moving from a hobby project to an important and also a commercial platform, as we were preparing the launch of our productized version of Travis CI.

Being notified by our customers that things weren’t working was and still is to this day my biggest nightmare, and we had to work hard to get all the right metrics and monitoring in place for us to notice when things were breaking.

It was impossible for us to reason about what is happening in our little distributed system without having any metrics or aggregated logging in place. By all definitions, Travis CI was already a distributed system at this stage.

Adding metrics and logging was a very gradual learning experience, but in the end, it gives us essential insight into what our system is doing, both in pretty graphs and in logged words.

This was a big improvement for us, and it’s an important takeaway. Visibility is a key requirement for running a distributed system in production.

When you build it, think about how to monitor it.

Making this as easy as possible will help shape your code to run better in production, not just to pass the tests.

The crux is that, with more monitoring, you gain not only more insight, you suddenly find problems you haven’t thought about or seen before. With great visibility comes great responsibility. We now needed to embrace that we’re more aware of failures in our system, and that we need to actively work on decreasing the risk of them affecting our system.

About a year ago, we saw the then current architecture breaking at the seams. Hub in particular turned into a major concern, as it was laden with too many responsibilities. It handled new commits, it processed and forwarded build logs, it synchronized user data with GitHub, it notified users of broken and successful builds. It talked to quite a bunch of external APIs along the way, all in one process.

It just kept on growing, but it was impossible to scale. Hub could only run as a single process and was therefore our biggest point of failure.

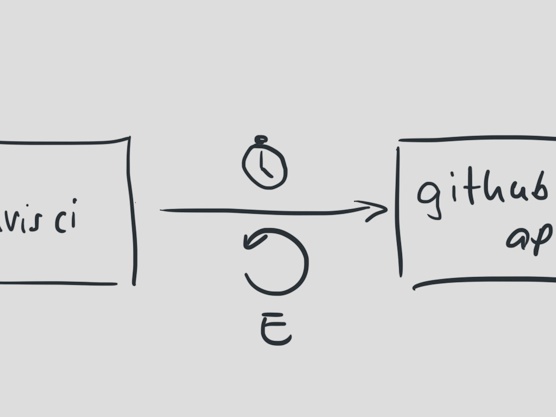

The GitHub API is an interesting example here. We’re a heavy consumer of their API, we rely on it heavily for builds to run. We pull build configuration via the GitHub API, we update the build status for commits, we synchronize user data with it.

Historically, when one of these failed, hub would just drop what it was working on, moving on to the next. When the GitHub API was down, we lost a lot of builds.

We put a lot of trust in the API, and we still do, but in the end, it’s a resource that is out of our hands. It’s a resource that’s separated from ours, run by a different team, on a different network, with its own breaking points.

We just didn’t treat it as such. We treated it as a friend who we can always trust to answer our calls.

We were wrong.

A year ago, something changed in the API, unannounced. It was an undocumented feature we relied on heavily. It was just disabled for the time being as it caused problems on the other end.

On our end, all hell broke loose. For a simple reason too. We treated the GitHub API as our friend, we patiently waited for it to answer our calls. We waited a long time, for every single new commit that came in. We waited minutes for every one of them.

Our timeouts were much too gracious. On top of that, when the calls finally timed out, we’d drop the build because we ran into an error. It was a long night trying to isolate the problem.

Small things, when coming together at the right time, can break a system spectacularly.

We started isolating the API calls, adding much shorter timeouts. To make sure we don’t drop builds because of temporary outages on GitHub’s end, we added retries as well. To make sure we handle extended outages better, we added exponential backoff to the retries. With every retry, more time passes until the next one.

External APIs beyond your control need to be treated as something that can fail anytime. While you shouldn’t try to isolate yourself from their failures, you need to decide how you handle them.

How to handle every single failure scenario is a business decision. Can we survive when we drop one build? Sure, it’s not the end of the world. Should we just drop hundreds of builds because of a problem outside of our control? We shouldn’t, because if anything, those builds matter to our customers.

Travis CI was built as a well-intentioned fellow. It assumed only the best and just thought everything was working correctly all the time.

Unfortunately that’s not the case. Everything can plunge into chaos, at any time, and our code wasn’t ready for it. We did quite a bit of work, and we still are, to improve this situation, to improve how our own code handles failures in external APIs, even in other components of our infrastructure.

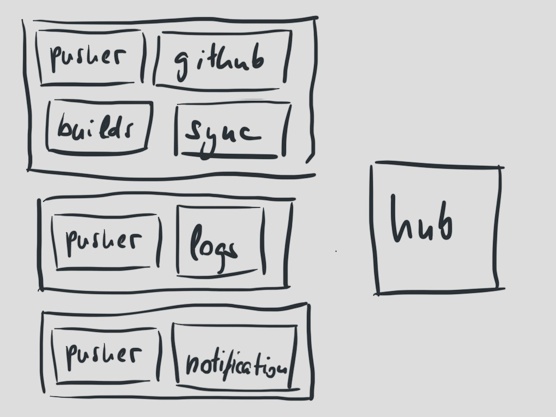

Coming back to our friend, the hub, the tasks it did were easy to break out, so we split out lots of smaller apps, one by one. Every app had its own purpose and a pretty defined set of responsibilities.

Isolating the responsibilities allowed us to scale these processes out much easier. Most of them were pretty straight-forward to break out.

We now had processes handling new commits, handling build notifications and processing build logs.

Suddenly, we had another problem.

While our applications were now separate, they all shared a single dependency called travis-core, which contains pretty much all of the business logic for all parts of Travis CI. It’s a big ball of mud.

This single dependency meant that touching any part of the code could potentially have implications on applications the code might not even be related to. Our applications were split up by their responsibilities, but our code was not.

We’re still paying a price for architectural decisions made early on. Even a simple dependency on one common piece of code can turn into a problem, as you add more functionality, as you change code.

To make sure that code still works properly in all applications, we need to regularly deploy all of them when updates are made to travis-core.

Responsibility doesn’t just mean you need to separate concerns in code. They need to be physically separated too.

Complex dependencies affect deployments which in turn affects your ability to ship new code, new features.

We’re slowly moving towards small dependencies, truly isolating every application’s responsibilities in code. Thankfully, the code itself is already pretty isolated, making the transition easier for us.

One application in particular is worth a deeper look here, as it was our biggest challenge to scale out.

Logs has two very simple responsibilities. When a chunk of a build log comes in via the message queue, update a row in the database with it, then forward it to Pusher for live user interface updates.

Log chunks are streamed from lots of different processes at the same time and used to be processed by a single process, up to 100 messages per second.

While that was pretty okay for a single process it also meant that it’s hard for us to handle sudden bursts of log messages, and that this process would be a big impediment for our growth, for scaling out.

The problem was that everything in Travis CI relied on these messages to be processed in the order in which they were put on the message queue.

Updating a single log chunk in the database meant updating a single row which contained the entire log as a single column. Updating the log in the user interface simply meant appending to the end of the DOM.

To fix this particular problem, we had a lot of code to change.

But first we needed to figure out what would be a better solution, one that would allow us to easily scale out log processing.

Instead of relying on the implicit order of messages as they were put on the message queue, we decided to make the order an attribute of the message’s itself.

This is heavily inspired by Leslie Lamport’s paper “Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System” from 1978.

In the paper, Lamport describes the use of an incrementing clock to retain an ordering of events in a distributed system. When a message is sent, the sender increments the clock before it’s forwarded to another receiver.

We could simplify on that idea, as one log chunk is always coming from just one sender. That process can take care of always incrementing the clock, making it easy to assemble a log from its chunks later on.

All that needs to be done is do sort the chunks by the clock.

The hard part was changing the relevant bits of the system to allow writing small chunks to the database, aggregating them into full logs after the job was done.

But it also directly affected our user interface. It would now have to deal with messages arriving out of order. The work here was a bit more involved, but it simplified a lot of other parts of our code in turn.

On the surface, it may not seem like a simplification. But relying on ordering where you don’t need to is an inherent source of implicit complexity.

We’re now a lot less dependent on how messages are routed, how they’re transmitted, because we now we can restore their order at any time.

We had to change quite a bit of code, because that code assumed ordering where there’s actually chaos. In a distributed system, events can arrive out of order at any time. We just had to make sure we can put the pieces back together later.

You can read more about how we solved this particular scaling issue on our blog.

Fast-forward to 2013, and we’re running 45000 build jobs per day. We’re still paying for design decisions that were made early on, but we’re slowly untangling things.

We still have one flaw that we need to address. All of our components still share the same database. This has the natural consequence that they’ll all fail should the database go down, as it did just last week.

But it also means that the number of log writes we do (currently up to 300 per second) affects the read performance for our API, causing slower reads for our customers and users when they’re browsing through the user interface.

As we’re heading towards another magnitude in the number of builds, our next challenge is likely going to be to scale out our data storage.

Travis CI is not exactly a small distributed system anymore, now running off more than 500 build servers. The problems we’re tackling on solving are still on a pretty small scale. But even on that scale, you can run into interesting challenges, where simple approaches work much better than complex ones.